I approached this essay a few ways. The first was by lying. I wrote a paragraph about going through rational and efficient stages– planning, outlining, writing, revising– and how my ideas morph miraculously and consistently into the written word. The second was by apologizing. Even as I wrote this, having rode roughshod over my own characterization of how I compose a paper, I realized that I might not have a writing process. Or, put differently, I realized that calling what I do a process– the way I use a Google doc to aimlessly wander through my mind– is probably too generous. The reality is that there are few tasks I approach in a less efficient or clear-cut way than the essay. I’ve rescinded that apology, and I’ve decided that it is a process (after all, it’s produced something, regardless of its quality). All of the inefficiencies– the verbal meandering, the pointless diversions– are part of the process that culminates in a final product. And my writing wouldn’t be the same without them.

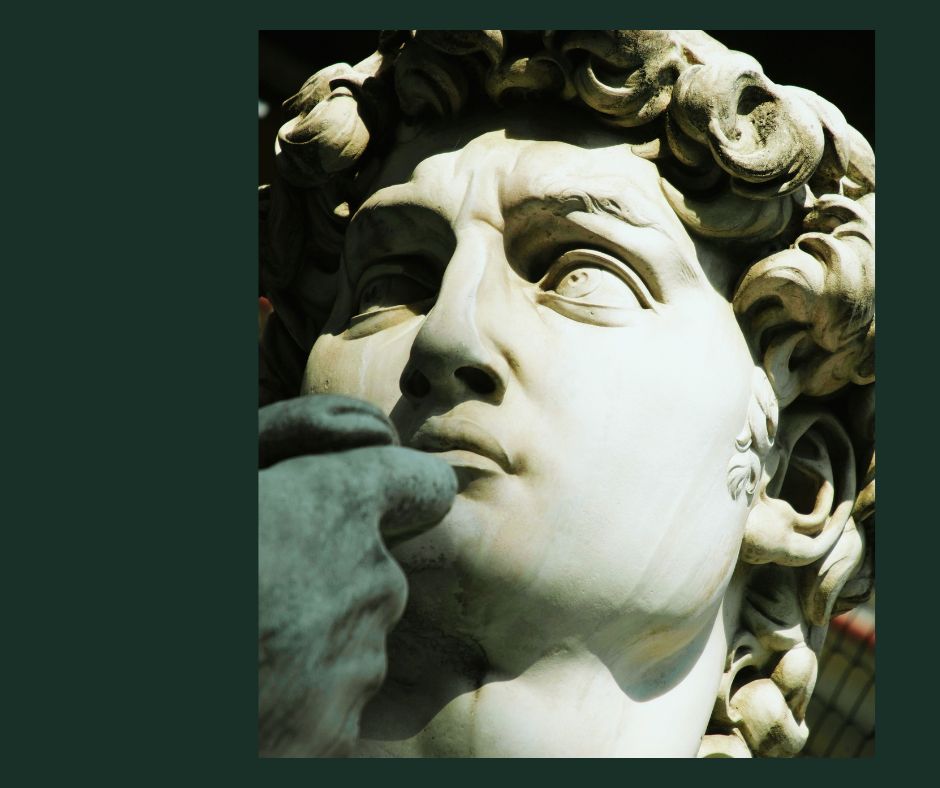

I start my process for every paper by acknowledging, despite my resistance, that I’m not Michelangelo. That’s probably the greatest epiphany I’ve had about writing. While other Renaissance sculptors used cast models before marking where to cut on a slab of marble, Michelangelo worked freehand. He saw his figures in the marble and worked to carve them out. And so his statues emerged, as Vasari wrote, like they were “surfacing from a pool of water.” I think a lot of writers see themselves as Michelangelos, about to make a masterpiece on the first try. We sit before a blank page, chisel in hand, hesitating on every word, fearing imperfection. I don’t exactly reject the analogy, but I reject the comparison between a slab of marble and a piece of paper. A writer needs an imperfect model to mold into a final product. A writer’s marble slab isn’t a blank page, it’s a first draft. To me, this is liberating.

“I think a lot of writers see themselves as Michelangelos, about to make a masterpiece on the first try.”

So when I have an idea about what I want to write, I just write. This leads to my first of many inefficiencies: I have never been capable of outlining. I’ve tried before to sketch my ideas in advance, but I can seldom stay loyal to it. I think writing and outline are fundamentally different processes. When I begin to actually type an essay, putting ideas on a page tends to lure me in directions that I hadn’t conceptualized. When I receive a prompt, I first write a few sentences that form the core of what I want to say. Then I turn to the trickier question of how to say it. For me, this involves sitting at my computer and typing until I feel satisfied that my idea lies somewhere on the page. My second writing inefficiency is that I’m a dogged rereader. Every sentence or two, my eyes creep back to the top of a paragraph, or sometimes the top of the page, to see how it’s fitting together. Like writing and outlining, I think writing and reading are different processes, and in my experience it’s only through the latter that I realize how uninteresting something sounds. It also gives me a constant sense of place– where I am, where I’m going, and how my ideas have accumulated. At the end of a paragraph I go back and make a series of deletions or menial changes (like switching the phrase “negative edits” after remembering that the word “deletions” exists).

Stemming from this is my third inefficiency: double-tapping the enter key and starting a new section whenever I draw a blank. I leave the job of connecting them for later, and sometimes I never do. I’ve written first drafts double the size of my final, including lengthy diversions that I eventually deleted. But I think the process, despite its inefficiency, is necessary for good writing. I try to let all ideas, all approaches to a prompt, play a role in my paper. Some, I discover, are better in my head than on the page. One thing I don’t let myself do on a first draft is check the word count. If I rush to close my draft before its ideas are actually fleshed out, my essay reads like I was played off the stage before my speech was over.

“A writer’s marble slab isn’t a blank page, it’s a first draft. To me, this is liberating.”

When my first draft is done, I have a roadmap of what I want to say, a block of marble that I can chisel. First I look at the little things I can correct– all the egregious things I did with the English language. Then I do something admittedly strange: I write an outline of how I had organized my thoughts in the draft, and how I should have. For me, it takes the completion of a work to understand how each sentence or paragraph functions as a part of the whole. Reduction and reorganization is the part of the writing process where I can really start to chisel my piece of marble, with a rough understanding of the essay having already revealed itself.

When it comes to cutting, I take Orwell’s advice to cut any word, sentence, or paragraph that doesn’t strengthen a piece of writing. More holistically, though, the editing process is really the art of seeing alternatives. I find myself going through my writing deliberately omitting words and sentences, and asking myself, Is it clearer and more concise without this? I swap paragraphs, rearrange what I have top to bottom, and pursue all the alternatives I can see– until any additional changes would, in my opinion, be detrimental.

And that, in sum, is my process. It’s a collection of inefficiencies that I’m still unable to escape, but which I’ve come to embrace. For me, organizing, writing, editing, and rereading don’t happen in phases; they all work concurrently. It’s a messy process that takes a lot of time, but the time, to me, is not wasted. Once I’m able to spend enough of it navigating around the idea, meandering in my mind, and building my block of marble, I can carve something out of it, chisel it down to an imperfect but acceptable product, until I’m finally, eventually, ready to type my name proudly and bring the process to a close.