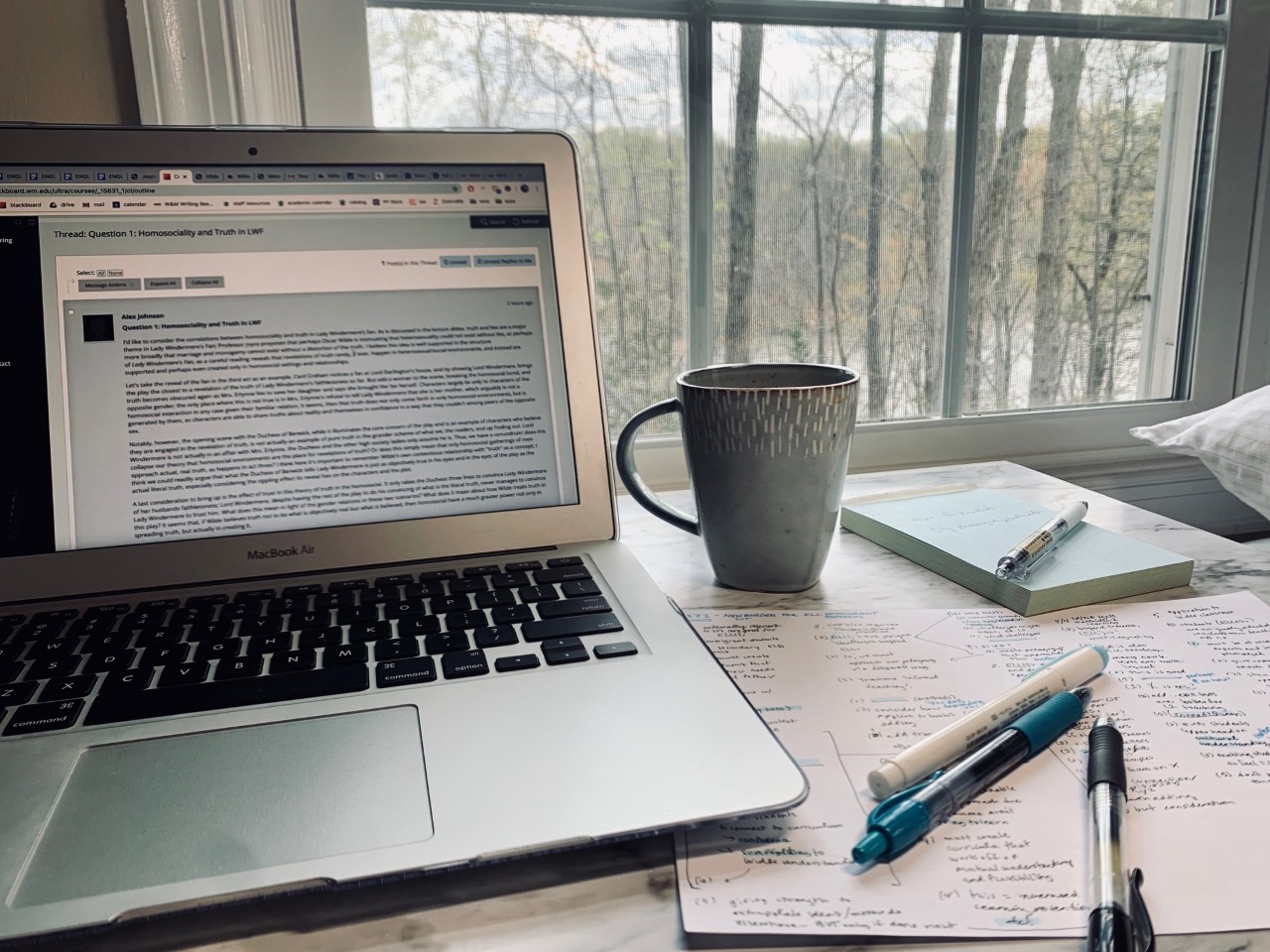

As colleges make the rapid shift to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, many professors are using discussion boards to replace in-class participation. At William & Mary, these online conversations take place through the Blackboard learning management system. Despite their relative simplicity, discussion boards remain unfamiliar to many students. They also generate a host of questions, as does any new form of writing:

- How long should my post be?

- How many replies are appropriate?

- How formal should I be?

- How do I cite a discussion post in a paper?

- How do I effectively reply to others?

- Am I doing any of this right? Help!

This post will provide a few answers to these questions.

What do you write about in a discussion post?

If your professor provided discussion post guidelines, start there.

But what if your professor simply said “go wild?” In that case, take some time to consider your usual participation in this class. Do you ask a lot of questions? If so, write posts that request clarification or opinions from other participants. Do you mostly respond to others? You may want to wait until a few classmates have posted initial thoughts, and then use your post to engage with their ideas. What if you don’t usually talk in class? If that’s you, you may find online discussion to be a welcome improvement!

Text-based online participation allows for more voices to be heard, and encourages a wider breadth of conversation. Don’t be afraid to get really detailed or really broad in your discussions; the content of your post can be a lot more extensive, varied, and tangential than a typical in-class comment would be since everyone can read it at their leisure.

What are the rules of behavior in discussion forums?

There will probably be a learning curve as you and your classmates figure out what discussion forum etiquette looks like for your class. Here are a few rules of thumb that apply to most online discussions:

- Be respectful. Just because you’re not face-to-face doesn’t mean words don’t still have power. When you criticize or disagree, be tactful and respond to the comment, not the commenter.

- Avoid repeating something that has already been said. Read the rest of the thread before starting so that you’re aware of the whole conversation.

- Reread your posts before you submit them. It’s always awkward to realize you’ve included a typo after you’ve already sent a post. (That said, don’t be afraid to edit your post after sending, if you need to fix things!)

- Keep your style relatively formal. Discussion boards may feel somewhat like social media, but they aren’t. Use complete sentences, minimize jokes or sarcasm, and keep emoji use to a simple 🙂 when needed.

- Make your posts meaningful. While you may want to express agreement, a post that just says “Yes!” isn’t helpful and clutters the thread. Be constructive, and try to think of a response or question that moves the discussion forward.

Do I Have to Cite Discussion Posts in Papers?

If you read a post that inspires further thinking, you may want to reference it in a later assignment. If you do, make sure to cite it, just as you would if you quoted someone from an in-class discussion. Both the MLA Style Center and the Purdue OWL’s APA Style Guide offer guidelines for citing discussion board posts. Here are two examples:

MLA:

Johnson, Alex. “Writing Discussion Posts” Writing Center Online Course, 28 March 2020. Blackboard Learn, https://blackboard.wm.edu/ultra/courses/123456/cl/outline.

APA:

Johnson, A. (2020). Re: Discussion Posts. Retrieved from

https://blackboard.wm.edu/ultra/courses/123456/cl/outline

If you’re feeling anxious about discussion posts, remember that others in your class may be as uncertain as you are. Reach out to a classmate or your professor if you have questions, or want feedback on how you’re doing. Try to embrace the medium; this is a chance to share your niche knowledge or chase a thought into interesting new corners. And, remember, the Writing Resources Center consults on any form of communication. If you’re feeling stuck or confused, book an online appointment!

See you over the web soon. Stay well.

It’s important to note that this isn’t a scatter plot graph; the smooth connecting line between the points shows that it’s not a discrete sentence for each level. Sometimes you may need a couple of sentences on level 3, and perhaps only half a sentence for level 2. The goal is to use the graph as a guideline, as a gesture where the paragraph is viewed as a vehicle of travel between different depths of thought.

It’s important to note that this isn’t a scatter plot graph; the smooth connecting line between the points shows that it’s not a discrete sentence for each level. Sometimes you may need a couple of sentences on level 3, and perhaps only half a sentence for level 2. The goal is to use the graph as a guideline, as a gesture where the paragraph is viewed as a vehicle of travel between different depths of thought.

The transition from high school into university is a large leap for many: students, parents, teachers, administrators, and, yes, even writing centers. Adjusting to the higher quality of writing and topics in numerous subjects that aren’t found in typical high school papers is a daunting task for both the consultant and the consultee, but it’s a necessary leap in higher education that fosters personal and intellectual growth.

The transition from high school into university is a large leap for many: students, parents, teachers, administrators, and, yes, even writing centers. Adjusting to the higher quality of writing and topics in numerous subjects that aren’t found in typical high school papers is a daunting task for both the consultant and the consultee, but it’s a necessary leap in higher education that fosters personal and intellectual growth.